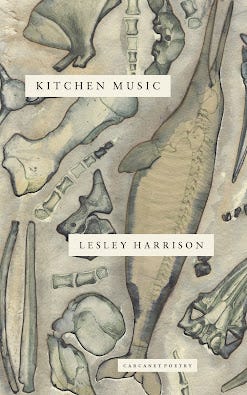

Kitchen Music: Lesley Harrison

This week's blog is written by Lesley Harrison, author of Kitchen Music, which is published this month. Use the code MAYBOOKS for 20% off the collection and free UK P&P.

As a poet, the whole idea of making a poetry of a place, of ‘languaging’ that place, interests me greatly. Language is the process by which we create ourselves, grammatically and referentially, as the figure-in-the-landscape. There is a phenomenological prioritisation of the self that happens as soon as we speak. But I wonder how far it is possible, by attending to the sounds and textures of our surroundings, to make yourself transparent.

I am very lucky to live on the very edge of the North Sea, along the high red cliffs of the Angus coastline. This is a quiet, watchful landscape: on the one side there are fields, then trees, and the grey shadows of the Grampian foothills; on the other, open sea. There is a sense of being at the temperate, friable edge of a much larger, older world. Many farms and settlements have fragments of ancient words and names embedded in them – caithlie, coultra, kettin, brechin – short syllables that snag the wind. There are traces of human occupation reaching back for four thousand years – cup and ring marks, ditches and small cliff forts beneath the gorse. At many points the coastal path overhangs the ocean below, and depending on the light you might see dolphins, or the row of giant wind turbines 11 miles out, or even the black back of a whale rising briefly, like a dark sunken moon.

Whales astonish me. The size and scale of their world is unimaginable, ungraspable. That these warm-blooded, sonorous, attentive mammals exist at all is blunt, everyday evidence of the proximity of the magical; of the fabulous, supra-natural, frangible world entirely beyond our own self-absorbed imaginings. The whale poems in Kitchen Music continue my obsession with the relics and aftermath of whaling: the polar ice, the language and intimacies of battle, their vast absence.

As language users, and as poets especially, we play with the texture of language, with the shape and lie of sounds in the mouth, with ‘language lined with flesh … the whole presence of the human muzzle’ (Barthes). Does our sonic landscape – wind, trees, rooms, traffic – reflect back in the qualities and adjustments of our own voice? The poets and poetries that intrigue me most are those who attend to the outer world and try to make language adequate to its surroundings, and not vice versa: most recently Caroline Bergvall’s Drift, Alice Oswald’s Nobody, Tim Cresswell’s Fence, all of Susan Howe. ‘Hugh MacDiarmid used to speak about the human brain being largely unused,’ said Edwin Morgan when discussing the multilingualism and sound experimentation in his own poetry. ‘I’m sure that’s quite true, and I think language is like that too.’

I’m very proud of Kitchen Music – it’s a very personal collection – and I am deeply indebted to Jeffrey Yang, Kirsty Gunn and Michael Schmidt for their encouragement, and to Eileen Bellamy and Jenny Elliott for their gorgeous cover artwork. It is such a complement and a privilege to have your writing so beautifully presented.

Watch Lesley introduce the collection.