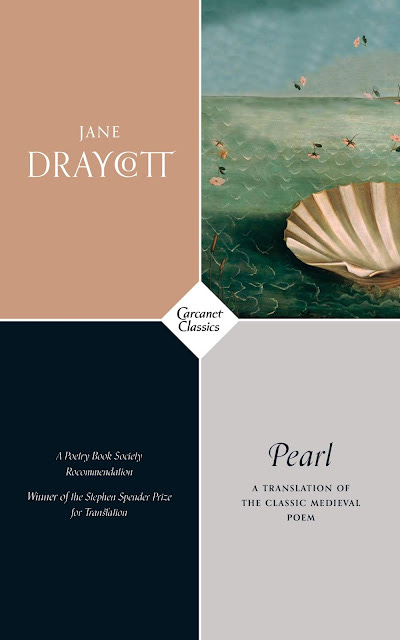

Jane Draycott: Translating 'Pearl'

This week's blog is written by Jane Draycott, author of Pearl, re-released as a Carcanet Classic this month.

In a dream landscape radiant with jewels, a father sees his lost daughter on the far bank of a river: ‘my pearl, my girl’. One of the great treasures of the British Library, the fourteenth-century poem Pearl is a work of poetic brilliance. Its account of loss and consolation retains its force across six centuries.

***

Then the power and perfume of those flowers

filled up my head and felled me, slipped me

into sudden sleep in the place

where she lay beneath me. My girl.

[Pearl, ll. 57-60]

Translation is a great teacher, a chance to climb inside another poet’s imagination, their ear, their poetics, and become an apprentice to their art. As I worked within the Pearl poet’s tight patterning of rhyme and repetition, the fractal effects of its echo and duplication, I understood better than ever how language gives birth to language, how sound engenders imagery and meaning.

In Zoran Anchevski’s poem ‘Translation’ the translator sleeps ‘on a pillow of someone else’s dreams’* and the beautiful, intricate 14th-century Pearl is surely a dream-poem like no other. An elegy for an infant girl, its Christian consolatio is framed in a relay of visions, from St John’s Apocalypse via Dante to the bereaved narrator’s glittering re-animation of his lost girl in a jewelled world touched with the north – quails and woodland, hawks in halls, water running in ditches.

By the time I reached the end of the first 60 ines, a transformative idea was rising in my ear, and the central repeating word pearl surfaced in its final iteration as something different- girl. I was aware of the side-step I’d made, but didn’t feel entirely off track or unfaithful. It was partly my own experience which had revised that moment but – much more strongly – the feeling within the poem that speaks across the centuries with such electric immediacy, the personal, psychological-emotional charge of grief, the near-confession that the Christian promise of eternal life is no real consolation.

The dream vision in Pearl is as much about the adaptive function of the imagination (what Heaney memorably called its role as part of our immune system) as it is a reworking of conventional literary tropes and the formalised consolations of religious doctrine. Like the vivid working of actual dreams, the pearl maiden appears within a few lines as both infant and fully grown woman, courtly maiden, object of love, perhaps the woman she might have become had she lived. In an almost hallucinatory fashion, she is also and at the same time the immaculate pearl which she wears on her own breast. She is the Virgin Mary, the immortal soul, the kingdom of heaven itself. To dreamer and reader the lost child is all these things simultaneously, the allegory deep-drilled, a fusion of powerful feeling and ideas not mutually exclusive.

That simultaneity seems to me to be absolutely a poet’s apprehension. The anonymous Pearl poet, assumed to also be the author of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight - translated with such flair in 2006 by Simon Armitage - is vivid and visionary in the manner that Eliot recognised in Dante: ‘It is a visual imagination... in the sense that he lived in an age in which men still saw visions’. We have the sense too that the Pearl poet does not, as St John did, write to create an account of a dream actually experienced, but that the very act of writing is the dream.

* transl. Sudeep Sen (Aria/Anika, Mulfran Press 2011)

Jane Draycott