Infinite in Finite: Andrew Wynn Owen

This week's blog is written by Andrew Wynn Owen, author of Infinite in Finite, which is published this month. Use the code SEPTBOOKS for 20% off the collection and free UK P&P.

What I say here will be a simplification of a long story, but here goes.

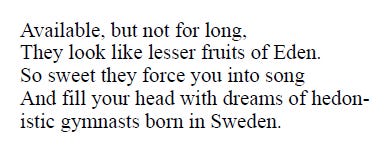

When I started putting proper time and thought into writing poetry, about sixteen years ago, I liked making patterns like this:

And so on. An iambic tetrameter (or whatever other form appealed). People told me they liked it — even, sometimes, had memorized it (and were grateful that it was the kind of work that you could memorize well). I liked that they found it humorous: particularly since the matters it treated with humour, desire and death, were abiding subjects for poetry. But I was not content. Why was I not content? Because new challenges would soon be needed, to produce the best work. The resistance of the medium was energising. ‘Difficulty is our plough.’

But which way were the most complicated (and so artistically-fruitful) challenges to be found?

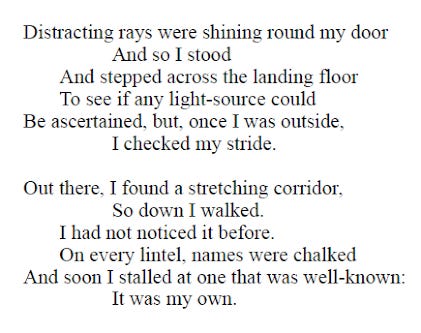

So began a search for new vistas, formal and contentful. I tried free verse, and liked it (loved it, at its best), but found it limited (in the wrong way) and anti-social (anti-social because the final shape was idiosyncratic, rather than a pattern that might be shared, across space and time, with other creators). It had variation, but lacked the kind of sustained pattern that would make that variation artistically valuable. Eventually, I began writing like this:

There was a more complicated pattern here, so more that could be done artistically, in pursuing and breaking the pattern, going with or against it. (I looked about for people who, in modern times, had written well in these kinds of forms, and found a good handful.) I presented this method at length in my first collection, The Multiverse. In this book, I’ve intensified the method, producing more sustained and intricate pieces.

I call the stanza on the cover of the book the ‘de Bruijn stanza’, after the Dutch mathematician whose eponymous sequence inspired its creation. About the de Bruijn stanza, a friend at a writing workshop said (I paraphrase), ‘These stanzas all have a distinctive rhythm. After reading a number of them, it becomes apparent. You really have invented a new form.’ My only objection was to say that it was not an invention, but rather a discovery (because I believe that the form existed before I brought it onto the page — this is because I am a realist about such forms). When I was younger I used to think, ‘People discover new animals every now and then. Why shouldn’t I discover a new form?’ And that’s what has happened. The de Bruijn stanza is, I think, a distinctive type — perhaps a natural kind, like donkey or badger.

But let’s put aside that particular stanza-form. What I want to emphasize is the general method of discovery. My hope is that people setting out on the path of writing poetry will be influenced by what I have been trying to do. It took me a long time to realise that this was the best, most reliable system for a poet. The realisation-process took up much of my energy. Now, you need not waste time on the realisation-process! Just dive in and make the artworks.

So I urge writers who are setting out to use the explosive creative energies of their setting-out on writing in this way, the polymetrical way. Free verse and monometrical poems are fine as well, sometimes. But the best free verse was written by people who had already honed these techniques, and even then they wrote it sparingly. Sure, write monometrically at first, but remember to grow beyond it, into polymetrical complexity: that is where the greatest expanse of poetical possibility is. As Wilbur said, ‘the beautiful changes’: ‘Your hands hold roses always in a way that says / They are not only yours; the beautiful changes / In such kind ways’.

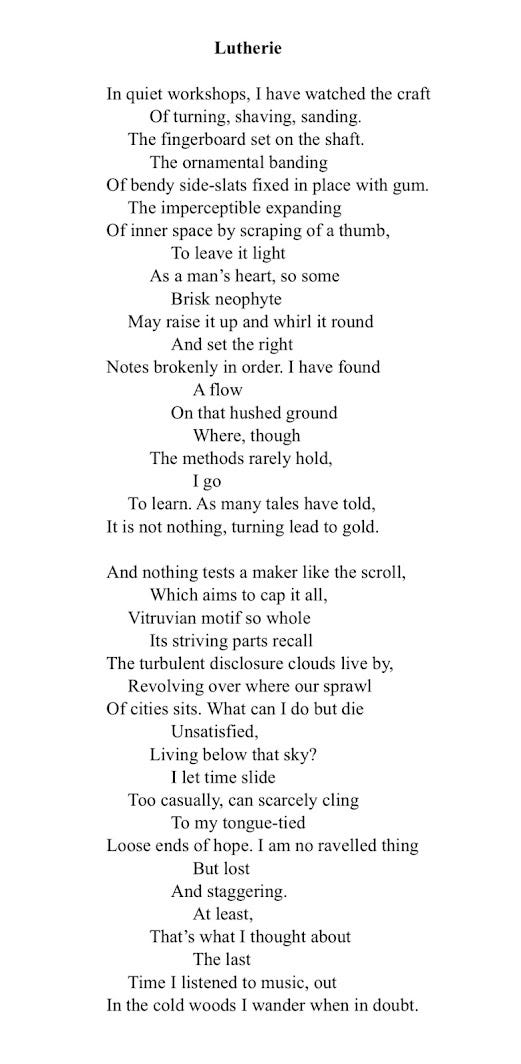

I’ll end with a poem I like, in a form that I hope others will catch hold of and run with. I have, so to speak, passed you the ball! Whoever you are, it is yours to go on with. I wrote this piece in the voice of a craftsman, a maker of violins, seeking meaning. The poem is about art, but also about our place in the world: about perplexity, grief, and joy, in the face of our limited knowledge. In the back of my mind were lines from Fernando Pessoa: ‘My heart, the deluded admiral / Who ruled a fleet of never-built ships, / Followed a route Fate wouldn’t admit, / In search of an impossible happiness.’

I hope someone reading will give the form a go — and more, make something with it. To that end, there is one last thing to say: form alone is not enough for an artwork. Nor is content. What is needed is a form-content unity that works. Here is the poem, in an extended version of the de Bruijn stanza:

Listen to Andrew read an excerpt from the collection.