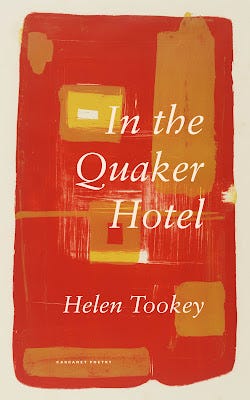

In the Quaker Hotel: Helen Tookey

This week's blog comes from Helen Tookey, whose collection In the Quaker Hotel is published this month. We're launching the collection on May 25th with Seán Hewitt - click here for more information and to buy tickets.

Use code MAYBOOKS for 20% off RRP on our website

This book had a very definite starting point. At some point early in 2019, I read a news story on my phone over breakfast which said (as I recall it) that over 50% of the world’s insect species have died out since 1970. I was born in 1969, so to me this story effectively said that over half of the world’s insect species have died out in the course of my lifetime – which seemed a terribly short span of time for such a huge amount of loss. Somehow, this link between the world-historical and the personal scale seemed to shock me, as nothing before had quite done, into a feeling of absolute grief at what we are in the process of destroying, and how rapidly we’re doing it.

As I walked to the station to get the train into town, to go to work, the first part of what became the poem ‘Amber’ began narrating itself in my head: When they told us the insects were dying / we finally understood it was over. We didn’t know how / to tell the children… It was one of those rare occasions when you feel as though you’re just taking dictation, writing down something that has come to you fully formed from somewhere else. Indeed, at first I didn’t even really understand why the poem went were it did – into a memory of a childhood holiday in Cromer (as all our family holidays were), another girl finding a big piece of amber (amber isn’t uncommon on the East Anglian coast, but this was an unusually large, beautiful piece), my envy that I hadn’t found it, spending the rest of the holidays convincing myself that every yellow pebble was a piece of amber. I didn’t have a conscious sense of why this memory was relevant, but I dutifully wrote it down as part of the poem, because it felt so definite. It was only afterwards that I could see how amber connected to the idea of insects dying out, how the recollection of the memory connected to ideas around what is and isn’t preserved, and how the poem set my own child-self into relation, or juxtaposition, with my present adult self and with the other ‘children’, those who are children now and therefore the ones facing this extremely uncertain future.

The concerns and, in many ways, the fields of imagery of the book spiralled out from there. I found myself writing a number of poems that connected back to those childhood holidays, those stays in guest-houses, and that opened up a train of thought about temporariness, fleetingness, human beings as only ever guests on this planet and, in a way, inside our own lives. (Jane Draycott’s 2016 Carcanet collection The Occupant was one book that I read and re-read during this time which helped inform this aspect of my own writing.) Inspired by two visits to southern France, I also found myself writing a lot of poems about water and light, about surfaces and thresholds – and about heat, very obviously a double-edged thing in our present times. All of this, again, connected to my idea of the book as exploring a kind of threshold moment, a facing-both-ways – looking back to childhood, looking forward to the uncertain future, my very strong feeling of the present as a kind of pivot-point.

The visits to southern France, in particular, and experiencing the light and heat there, helped me to construct a kind of image-landscape for the book that would feel different, in terms of colour and temperature, from those of my previous collections – especially City of Departures, which had a very northern-European feel to it. I wanted, for this book, to try to create the sensation – if not always the literal image – of a group of people walking through a bright, hot landscape, trying to make sense of things. I think some of Eliot’s imagery from ‘What the Thunder Said’ was at the back of my mind here; another, more contemporary reference point was Carola Luther’s brilliant and moving sequence ‘Letters to Rasool’, which I read when it was published in PN Review in 2019 (and which is now included in her wonderful collection On the Way to Jerusalem Farm [Carcanet, 2021]). I admired the way this sequence used a slightly near-future perspective as a means of addressing the now, and this was something I also tried to do in a number of the poems and pieces in In the Quaker Hotel, even while they are also set in real, sometimes even named, places, such as Anglesey’s Parys Mountain, by the Mersey at New Brighton, or in Elizabeth Bishop’s childhood home in Nova Scotia. Ultimately, I wanted to try to create the sense of places and moments that might hover disconcertingly between past, present and future, leaving it open to interpretation what exactly this world is that the people in the poems inhabit, what they can understand of it, and where they might go next.

Watch Helen introduce the collection