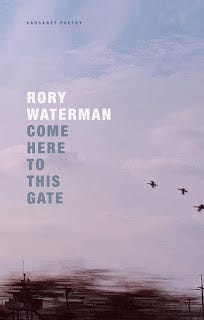

Come Here to This Gate: Rory Waterman

This week's blog, 'YALLERY BROWN IS BACK!', is by Rory Waterman, author of Come Here To This Gate, which is published this month. Use the code APRILBOOKS for 20% off the collection and free UK P&P.

Let me tell you about Yallery Brown. He is a tiny being, obviously old, sports a long and unruly yellow beard, and appears to be made of mud, earthly matter, and possibly some excrescences too. Perhaps you’ve encountered him. One summer day, a young and feckless farm labourer called Tom is walking to the farm, when he hears what he thinks is the cry of a baby coming from a spinney. He soon discovers that, instead, it is Yallery Brown, supine and pinned down by a big flat rock. Tom removes the rock, and Yallery offers to do him a favour in return. What would Tom like, asks Yallery: does he want ‘the liveliest lass in town’ for a wife? Would he instead appreciate great riches? Or would he like to have help with his work? He opts for the latter, thanks Yallery, and is told in no uncertain terms never to thank him again. He has no cause to do so, trust me, and of course everything soon goes tits up.

We do not know the origins of the tale, but its first written retelling was collected by Marie Clothilde Balfour, and published (in Lincolnshire dialect – think lots of extra vowels, enough to make Farmer Wink sound like Jeremy Vine) in the then-burgeoning journal Folklore in 1891. According to Joseph Jacobs, who retold the tale in his 1894 book More English Fairy Tales, the story had been relayed to Balfour by a farm labourer called Tom, who gave his name to its hapless fully-human protagonist. Jacobs suggests the storyteller was ‘adapting a local legend to his own circumstances’. More recently, Maureen James, in her 2013 PhD thesis Investigating the Legends of the Carrs, has impressively, and plausibly, traced this man, suggesting he was probably a labourer called Thomas Laming, who worked at a farm near the village of Redbourne. Some people thing Balfour might just have made it all up, because the story has no obvious direct analogues (beyond its obvious connection to the ‘spirit in the bottle’ tale type), which is unusual for a folk tale.

This is all very fascinating if you’re interested in such things, and I am. But I also don’t believe folk tales should be in aspic, regarded only as fixed documents from the past. They’re not then living folk tales, in one crucial sense, because they can no longer move with the ‘folk’. Adaptations of folk tales are, as far as I’m concerned, not really adaptations at all: they are – or, rather, can be – mutations, different and new counterpart versions of the real thing, with equal rights. Folk tales must live in order to remain alive. (They also need to be told, transmitted orally, away from the worlds of copyright and perfect binding, but that’s a blog post for a different day – and, as Alan Partridge says, I’m making a point about something else.) There are several versions of ‘Yallery Brown’ in print, all in prose, and some are wonderful. One of my favourites is Kevin Crossley-Holland’s, published in the 1990s, though it keeps fairly close to the earliest extant version. My least favourite is this cloying American thing, which is apparently – and I quote from the YouTube channel page – ‘for teenagers’, though I remember being a teenager and I’m not convinced the authors (I assume it was written by committee) do. In any case, I have no problem with them altering the original almost beyond recognition. Mick Gowar wrote a superb version of the story for primary school children about twenty years ago, and he gives them a lot more respect. He also invents or ‘alters’ many details, including the tale’s ending, making it gruesome in a way that might have given Roald Dahl pause for thought. He makes no acknowledgment of this ‘change’ in his wee book – and why should he?

In all cases, though, these versions return us to an otherwise romanticised, unmechanised, bucolic past none of us has ever really experienced. Come Here to This Gate contains four versions of Lincolnshire folk tales – ‘Yallery Brown’, ‘The Metheringham Lass’, ‘The Lincoln Imp’ and ‘Nanny Rutt’ – in a section that comprises about a fifth of the book and is in some senses quite a departure from everything else in it. Two of them otherwise almost exclusively exist orally – though in truth they’ve all largely been forgotten, and I don’t think I know anyone from ‘back home’ who knew them before I started jabbering on about them. Mine are all set in the modern world of smashed Red Walls, drive-thrus on roundabouts, moral panics, despoliation, casualised labour, rampant commercialisation, and global catastrophe. Initially, I’d intended to title the section of the book that contains them ‘Lincolnshire Folk Tales Redux’, but I removed that last word, and why not? They’re mine, and they’re also yours. My protagonist in ‘Yallery Brown’ isn’t Tom, he is Will: my poem is (he’ll kill me for this) about my friends William Jackson and, to a lesser extent, Sarah Durrant, and their two kids, Emrys and Francis. William is responsible for the images used on the covers of my first and third collections, Tonight the Summer’s Over and Sweet Nothings, and the four of them live a long way from Hibaldstow, so I’ve changed the location too. I only hope this all annoys some purse-lipped academic folklorists somewhere. In most cases they’re rather more removed from the ‘folk’ than I am, whatever the people in their academic networks might tell them.

I could turn onanistic literary critic here, and discuss the ways in which ‘Yallery Brown’ is a clever cautionary tale, and how I’ve worked with that. It is, and I have keenly tried to do so, but I’ll leave you to decide out for yourself. My version certainly isn’t for children, though I suspect a lot of them would like its impishness. Here is an excerpt:

Then he said, ‘What you let out beneath

that tombstone, my lad, you can’t understand,

and whether you take it or leave it,

that much will stay true. But think: your poor hands’ –

he wank-waved my way – ‘they are yet

to have some time off. I could give you a wife

who will love you, somehow. Or your job:

it could all do itself while you sit in the grass,

or stay home and twiddle your knob.

Just say which you want.’ It was tempting. I mulled:

love? There’s enough time for love

to sort itself out, so I thought (I was young),

but no work to do? Lord above!

Maybe I’ll go home and surf the net

for ladies, or go down the pub

and she will be waiting for me, so I thought.

‘Work, please.’ He nodded, then rubbed

his billiard-ball belly, then nodded again.

‘It’s granted!’ ‘Well, thank you’, I said,

though not with conviction. He flew in a rage.

‘You must never thank me! No shred

of a thank you I’ll hear, you grateful young sod!’

He was flailing and gritting his teeth

and pounding the clods with his clod-coloured boots.

‘Okay!’ I cried. Then, with relief,

I saw he was turning to trog on his way,

and he bounded from molehill to molehill,

but his voice carried back, bringing with it a laugh:

‘Just call when you need me, young Will:

I’m Yallery Brown. Say my name, and I’ll come.

But’ – and at this, he looked back –

‘don’t thank me again, or I’ll leave you for good.’

Then the sprightly sprite danced up the track

and out of my life.

And into yours, if you buy the book, which I have divined that you are certain to do.